How Better Warehouses Increase Trade in Africa

Kuwait-based Agility Logistics Parks customers can log-on to view contracts and make payments.

UK MOD personnel can log-in to the GRMS portal to schedule household relocation shipments.

Kuwait-based Agility Logistics Parks customers can log-on to view contracts and make payments.

UK MOD personnel can log-in to the GRMS portal to schedule household relocation shipments.

As environmental, social, labor and governance imperatives come into sharper focus, the business case (again) for putting sustainability at the core of a company’s strategy.

Growing evidence suggests that businesses everywhere are putting sustainability at the core of their strategic thinking, planning and operations after decades of disconnect between their stated objectives and actions.

Sustainability is finally being embedded into business activity. One reason is that corporate data and academic research have begun to show a return on sustainable initiatives and practices, particularly at companies willing to broaden their definition of Return on Investment and adopt longer time horizons.

Another reason is the growing clamor from a spectrum of stakeholders – consumers, B2B customers, insurers, institutional and individual investors, regulators, community leaders, watchdog groups, employees and job candidates – for companies to demonstrate that they are responsible actors.

The sustainability movement is maturing. Considerations about social and environmental impact are shaping nearly every facet of corporate activity – nowhere more than the supply chain.

“Customers used to think about things in isolation like greening a warehouse, measuring CO2, or getting more visibility into their suppliers,” says Mariam Al-Foudery, Agility Group Chief Marketing Officer, who oversees sustainability and corporate social responsibility.

“Now more customers are looking at the whole supply chain and identifying practices that are connected and mutually reinforcing, things that have impact across business units and operational locations over the long-term.”

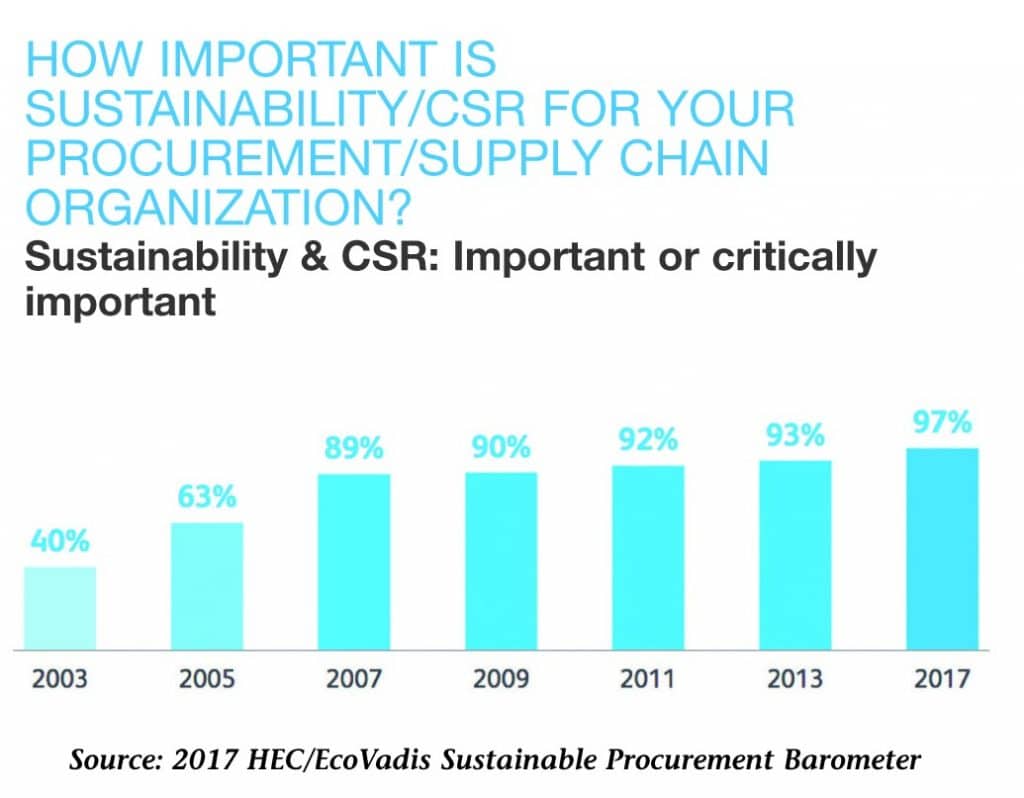

In a 2017 survey by EcoVadis and the HEC Paris business school, 97 percent of procurement officers surveyed listed sustainability as one of their top five priorities. Seventy-five percent of responding companies said they were using sustainability and corporate social responsibility criteria when selecting new suppliers.

Sustainable businesses try to meet the needs of the present generation without compromising the ability of future generations to meet their needs. They focus on good treatment of employees, impact on the environment, impact on local communities, and business relationships with suppliers and customers.

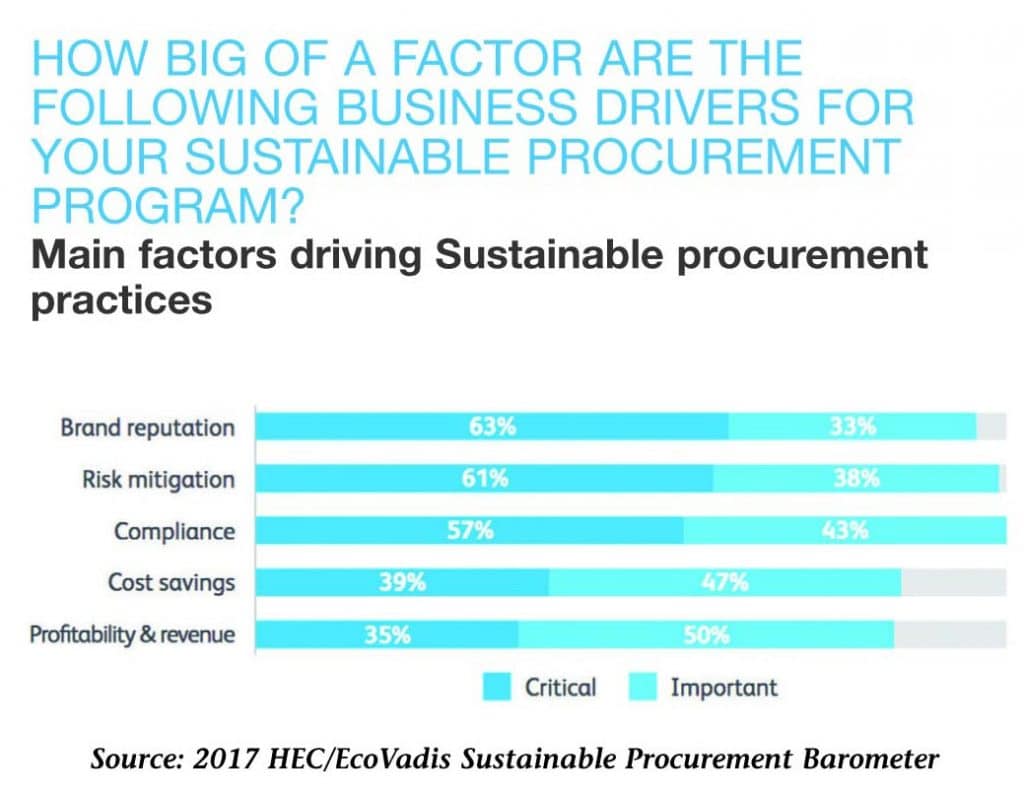

“Sustainable procurement is no longer a nice-to-have – it’s an integral business function responsible for protecting and improving brand reputation, driving revenue and mitigating business risk,” says Pierre-Francois Thaler, co-CEO of EcoVadis, an independent group that provides business sustainability ratings and analysis.

Yossi Sheffi, director of the MIT Center for Transportation & Logistics, says sustainability advocates have succeeded in framing the issue as one of “profits versus planet” or “societal good versus corporate evil.” He says that narrative ignores the role of businesses and their supply chains to provide jobs and deliver improved living standards. Sheffi argues that there is a difficult balance to strike and that the real friction is between those demanding environmental stewardship and people who seek jobs and affordable goods.

“Companies are championing their environmental credentials in glossy reports, speeches and media interviews,” Sheffi writes. “At the same time, however, many will admit, off the record, either that they do not believe in the need for this effort, or more commonly, that current initiatives do not meet any reasonable cost-benefit test even if global warming is real and the danger acute.”

Others insist there is mounting evidence that sustainability adds real value.

“Embedded sustainability efforts clearly result in a positive impact on business performance,” according to a Harvard Business Review article co-authored by Tensie Whelan, director of the Center for Sustainable Business at New York University’s Stern School of Business. (See Q&A on page 10).

Whelan and her co-authors argue that sustainability delivers significant cost savings from increased operational efficiency and that it drives companies to innovate by creating better processes, new products and equipment, and improved working conditions.

When sustainability is part of corporate DNA, it can “engender enthusiasm from employees, customers, suppliers, communities and investors,” the HBR authors conclude.

The Sustainable Business Council says there is ample research to show that sustainability lowers the cost of capital, results in better operational performance, and has a positive effect on stock price. Sustainability is a major factor in building and protecting corporate value, the SBC says. Consulting firm McKinsey has estimated that the value at stake from sustainability concerns is as high as 70% of earnings before interest, taxes, depreciation and amortization.

“Forty years ago, the bulk of a company’s value linked directly to its tangible assets,” the SBC says. “Now only about a fifth relates to a company’s financial performance and physical assets. The rest reflects intangible assets like brand, intellectual property, and whether a business has a social license to operate.”

When sustainability is part of corporate DNA, it can “engender enthusiasm from employees, customers, suppliers, communities and investors.”

Source: McKinsey Sustainability & Resources Productivity

Like its customers, Agility is taking aggressive steps to get greener. It is working with carriers to slash CO2 emissions, rethinking warehouse construction and management, piloting use of solar energy in building cooling, and investing in energy-recapture technology for trucks.

Mindful of its social impact, Agility pioneered protections and standards for workers in the Middle East more than a decade ago and has been a leader in sharing best practices and publicly advocating for stronger protections. In 2017, Agility introduced its first stakeholder policy, laying out goals and commitments to protect the environment, safeguard workers rights, improve communities where it operates, and be responsive to the needs and concerns of a variety of different interests.

“The biggest challenge for us and most logistics providers is on the customer side,” Al-Foudery says. “Customers want strategies, tools and technology to help them meet their sustainability goals.” One such tool gives Agility customers the ability to compare and optimize the environmental impact and cost of individual shipments using a nearly infinite variety of shipment types, routes, load sizes and configurations, and other factors.

A leading apparel powerhouse approached Agility with the goal of building sustainability into the design and manufacturer of its vast, globally sourced product line. Agility worked with the customer to create an information and standards framework and to build measurement and performance targets into its supply chain.

The apparel customer’s objective is a low/zero-impact, closed-loop supply chain: dramatic cuts in CO2 emissions and energy per unit of manufacture; facilities running 100 percent on renewable energy; 0 percent waste; doubling of supply chain efficiency every 18 months to two years.

“That can be scary, but customers with big, ambitious goals are sometimes the easiest to work with because they’re totally committed. They will take risks in order to become leaders,” Al-Foudery says. “They’re ready to innovate and break from established practices and willing to reward partners who help them achieve their goals.”

Sustainability efforts by consumer products companies and retailers typically get more visibility than those of B2B companies.

Alarmed by oceanic pollution, Nestle, Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola and Unilever are among those searching for alternatives to plastics from fossil fuel polymers.

“The typical consumer company’s supply chain creates far greater social and environmental costs than its own operations, accounting for more than 80 percent of greenhouse-gas emissions and more than 90 percent of the impact on air, land, water, biodiversity, and geological resources,” McKinsey says. “Most of the environmental impact associated with the consumer sector is embedded in supply chains.”

Ethical Corp. estimates that there are about 400 sustainability labels, including Fairtrade, which got its start in 1992 but is being overtaken by alternatives. Sainsbury’s, the UK supermarket chain, is among those that have shifted from the third-party Fairtrade certification, creating its own “Fairly Traded” label.

Unilever and Nike are recognized leaders on environmental and social initiatives. Campbell Soup works with farmers to optimize fertilizer use and improve soil conservation. Walmart gives suppliers incentives for their sustainability performance. Alarmed by oceanic pollution, Nestle, Procter & Gamble, Coca-Cola and Unilever are among those searching for alternatives to plastics from fossil fuel polymers. Target, Keurig and others are pushing suppliers of industrial plastic items such as crates and trash bins to use more “post-consumer” material.

The safeguarding of worker rights and improvement in working conditions is often the most difficult issue on the sustainability agenda.

Five years after the Rana Plaza factory collapse that killed 1,100 garment industry workers in Bangladesh, independent assessments report improvement in factory safety and monitoring by the government and local companies. But two organizations representing western brands and retailers recently said local authorities still aren’t prepared to assume responsibility for policing safety standards.

Worker rights can be a contentious issue even for global leaders such as Nike, which developed many of the best practices now used by apparel brands and manufacturers. Nike has voiced objections to advocacy groups positioning themselves as third-party auditors, arguing that there is a conflict of interest for groups that are both campaigning and auditing. For their part, advocacy groups say many audits go too easy on brands and manufacturers.

But failure to tackle environmental and social risks can have punishing consequences. Apparel companies that contracted with Rana Plaza garment makers fell from lists of most-reputable companies in the aftermath of the tragedy. Aussie GrainCorp reported that drought cut its grain deliveries by 23 percent and led to a 64 percent drop in 2014 profits. Unilever estimated that it loses 300 million euros a year as worsening water scarcity and declining agricultural productivity contribute to higher food costs.

It is through experimentation and innovation, not spreadsheet projections, that viable sustainable business models emerge.

Forum for the Future, an international sustainability nonprofit, says the companies set to benefit are those that can “capture the less tangible benefits as well as direct financial savings, for example, the clear reputational benefits of the initiative.”

The business-case numbers “are much ‘softer’ than decision-makers are used to,” the Forum says. As a result, “companies get stuck in a vicious cycle: they want a business case before giving permission to go-ahead with a project, but the information to build a business case can only be generated from the experience of going ahead.”

George Mason University professor Gregory Unruh says it’s time to look at the business case for sustainability a bit differently. “Multi-dimensional sustainability value is just hard to fit into a discounted cashflow analysis,” he writes.

Despite being hard to measure, Unruh writes, “investors are now realizing that sustainability performance feeds the long-term bottom line. And that’s causing managers to question traditional business thinking. So instead of spending time building a perfect business case, many are pursuing business model innovation experimentation, taking a page from Silicon Valley start-ups. It is through experimentation and innovation, not spreadsheet projections, that viable sustainable business models emerge.”